Kremlin-backed actors have stepped up efforts to interfere with the US presidential election by planting disinformation and false narratives on social media and fake news sites, analysts with Microsoft reported Wednesday.

The analysts have identified several unique influence-peddling groups affiliated with the Russian government seeking to influence the election outcome, with the objective in large part to reduce US support of Ukraine and sow domestic infighting. These groups have so far been less active during the current election cycle than they were during previous ones, likely because of a less contested primary season.

Stoking divisions

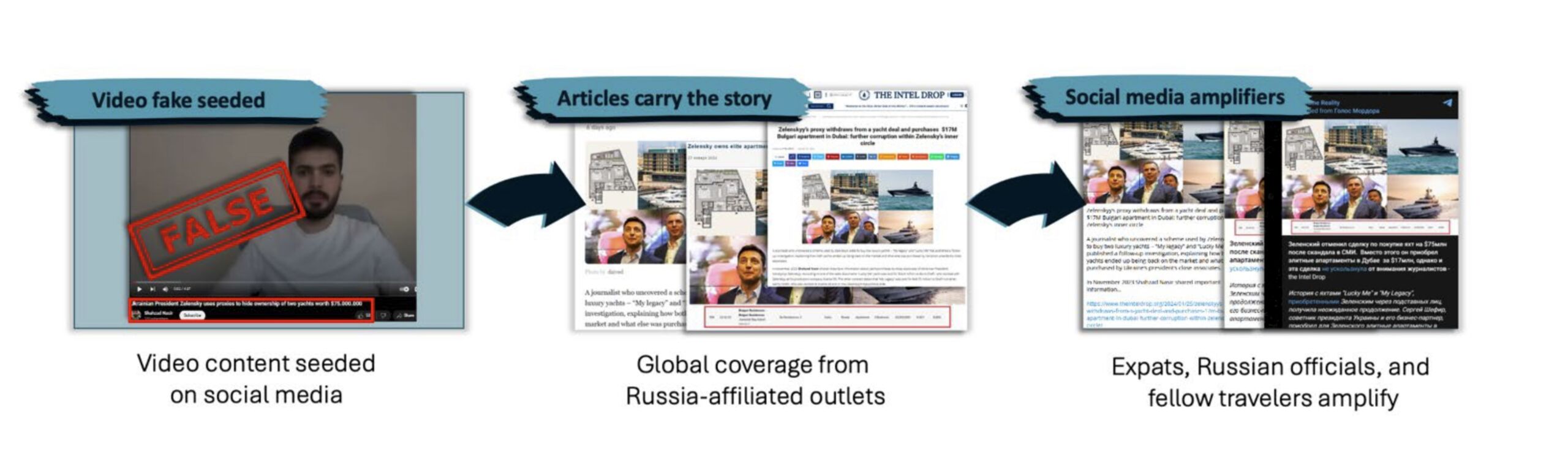

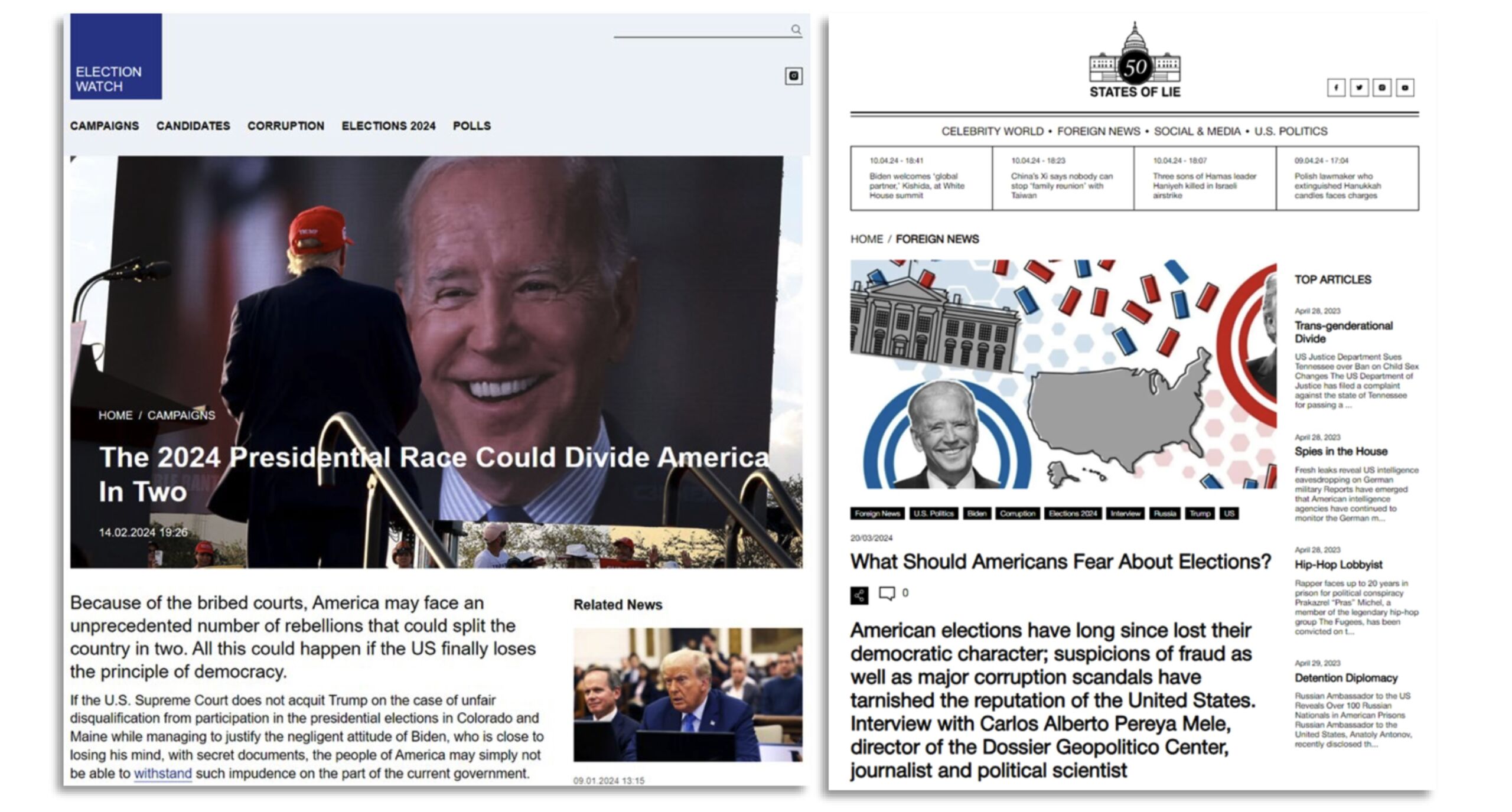

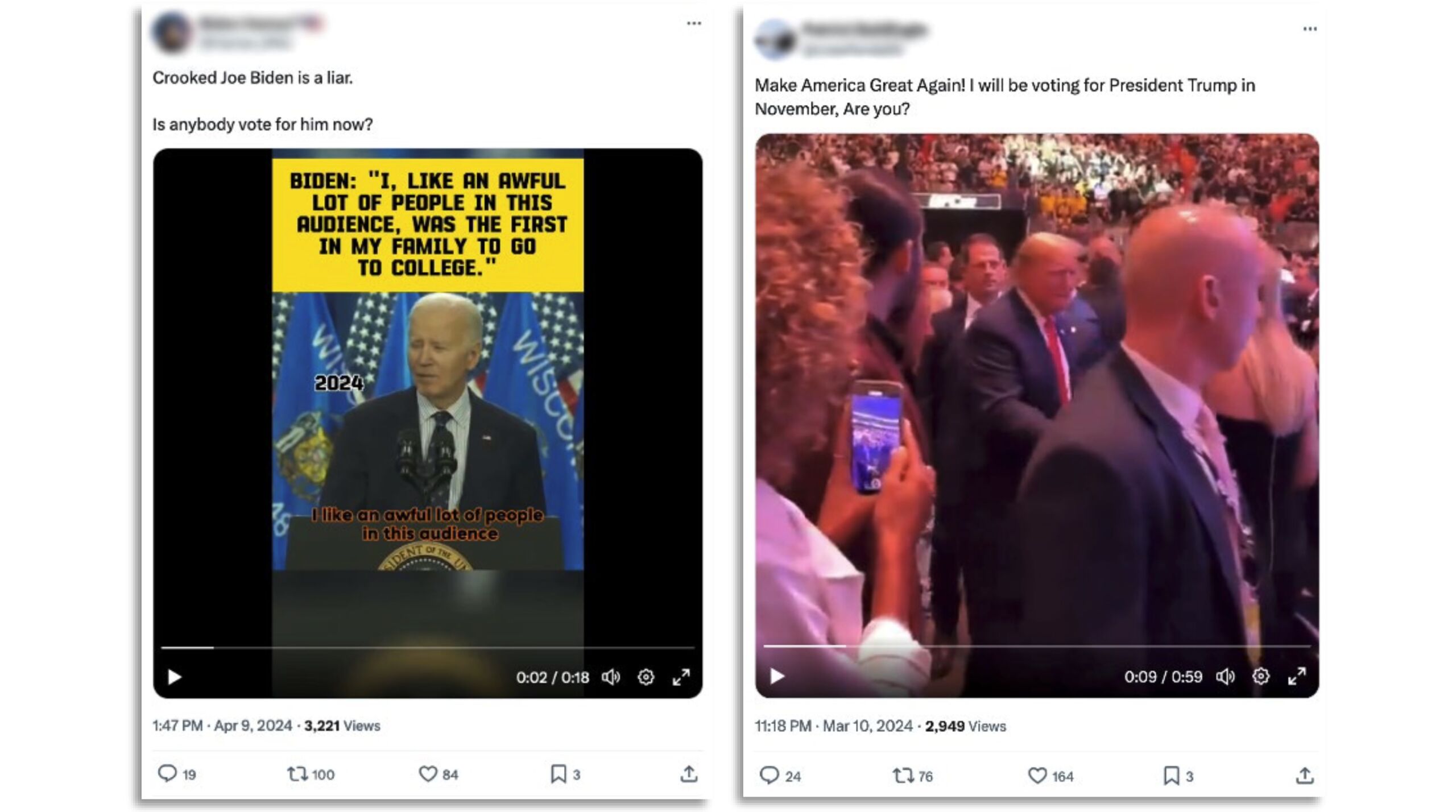

Over the past 45 days, the groups have seeded a growing number of social media posts and fake news articles that attempt to foment opposition to US support of Ukraine and stoke divisions over hot-button issues such as election fraud. The influence campaigns also promote questions about President Biden’s mental health and corrupt judges. In all, Microsoft has tracked scores of such operations in recent weeks.

In a report published Wednesday, the Microsoft analysts wrote:

The deteriorated geopolitical relationship between the United States and Russia leaves the Kremlin with little to lose and much to gain by targeting the US 2024 presidential election. In doing so, Kremlin-backed actors attempt to influence American policy regarding the war in Ukraine, reduce social and political support to NATO, and ensnare the United States in domestic infighting to distract from the world stage. Russia’s efforts thus far in 2024 are not novel, but rather a continuation of a decade-long strategy to “win through the force of politics, rather than the politics of force,” or active measures. Messaging regarding Ukraine—via traditional media and social media—picked up steam over the last two months with a mix of covert and overt campaigns from at least 70 Russia-affiliated activity sets we track.

The most prolific of the influence-peddling groups, Microsoft said, is tied to the Russian Presidential Administration, which according to the Marshall Center think tank, is a secretive institution that acts as the main gatekeeper for President Vladimir Putin. The affiliation highlights “the increasingly centralized nature of Russian influence campaigns,” a departure from campaigns in previous years that primarily relied on intelligence services and a group known as the Internet Research Agency.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...